|

Introduction

I began this photographic study in 1984,

following the seasons and my intuition through Bali, Java, Sumatra,

Sarawak, Thailand, Burma, Nepal, and India. After returning to New

Zealand, my birthplace, for a brief rest, I continued on to remote

regions of Australia and the Solomon and Vanuatu islands in the

Pacific. In part it was due to an interest in human culture that I

undertook the journey comprising the ‘Spirited Earth’, but in the

main it was born from a desire to explore the complex visual

symbols, philosophies, universal archetypes, emotions and aesthetics

contained within traditional performance, and in particular, the

bonds between peoples and their environment.

The theatrical version of the

Balinese deity Tjintiya - the Divine Androgyne, greeted me at the

beginning of my journey; an ancient symbol of the union of opposites

and original unity of life ushering me into the mystic and mythical

realm. Several years after this encounter, while I was in the South

Pacific islands of Vanuatu, photographing against the setting sun a

masked personification of an entity believed to appear to the

recently deceased, my camera jammed irreparably - ending the journey

with a vision as powerful as at its start.

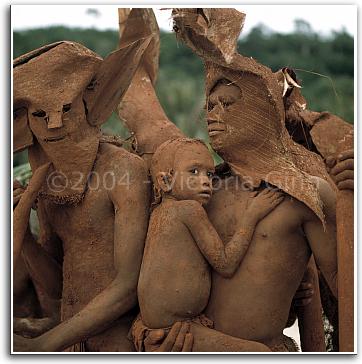

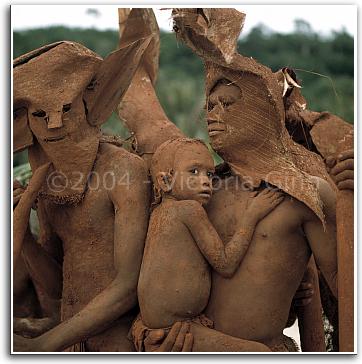

In the course of my travels I was

privileged to be shown and entrusted with documenting both sacred

and secular performance: the dances of creation stories, exploits of

mythical cultural heroes, visions of deities, rituals of the hunt,

ceremonies of initiation, funerary rites - the ‘performers’ actually

manifesting or becoming in the process of expression the

divine-consciousness, sorrowful king, flying monkey hero, ghost,

monster, initiated adult, ancestral spirit and so on. The images

come from various cultural and religious performance traditions, but

all communicate via the language of signs-gesture, colour, costume,

expression -to convey a meaning that has been handed down for

generations, and to lead the spectator and performer into a

consciousness of life beyond the perimeters of the everyday. They

are performances to entertain; instil moral and spiritual values in

the young; preserve traditional identity; give form to the subtle

truths and insights of the heart; pass on local myths; encourage

fertility and harvest; establish models of perfection; commune with

deities; initiate the young into knowledge of the mysteries;

maintain an equilibrium between the forces of light and shadow;

assist spirits of the dead to return to their places of re-birth-and

through all this to seek to maintain the unique and delicate beauty

comprising human culture. |

I did not undertake any research prior

to my journey and for the ‘anthropological’ meaning behind the

various performances I consulted the works of numerous scholars

post- journeying; I relied primarily, however, on the people

themselves to educate me. They told me the myths and fables of their

clans and explained how many of the dances and rituals were left as

gifts to them by their ancestors, or taught to them in dreams. Often

these ageold

performances have acquired varying interpretations as they passed

through the generations - sometimes the dance alone is all that

remains, its meaning lost entirely or carefully guarded by initiates

and adepts.

Some of the performers are from the

last generation to practise the traditional dances and rituals in

the true sense of expression and since my journey in the 1980’s many

of this generation have passed away and/or the original spiritual

function of the performance has been subsumed into spectacle.

Modernization, with its capitalist mentality has discouraged

indigenous traditions as ‘backward’ and in eroding cultural

individuality and self-esteem has created a potentially lethal sense

of displacement amongst

the younger generations of once autonomous tribal societies;

democracy has put an end to royal patronage of dancers; and the

unrelenting invasiveness of missionaries, who have moved to outlaw

tribal ‘heathenisms’, have all weakened traditional bonds. However,

some national governments have had the foresight to protect the

privacy of the more fragile cultural traditions.

Though documentary in their

significance the images represent a ‘creative collaboration’ between

myself and the participants and were given to me out of pride in

culture and the belief that I would help to ensure the protection

and place of traditional dance and culture amongst the wisdoms of

the world.

Victoria Ginn

This portfolio represents just a

small representation of the 47 photographs in the exhibition. The

book The Spirited Earth: Dance, Myth, and Ritual from South Asia

to the South Pacific (Rizzoli, New York, 1990) ISBN

0-8478-1167-0 contains most of the series of 200 images.

A New Zealand Centre for Photography touring exhibition.

More images

can be seen on

www.victoriaginn.co.nz |